|

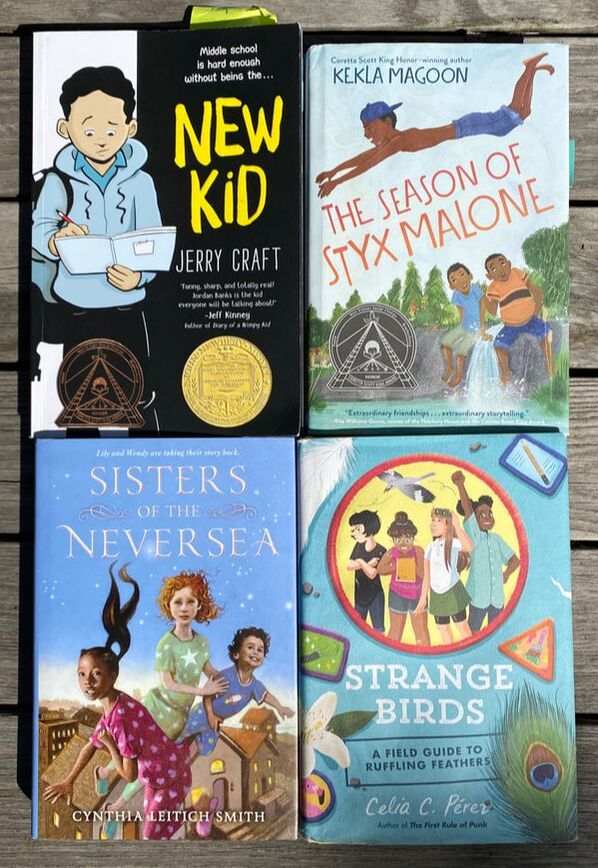

How comfortable are you with people whose backgrounds differ from yours? Are you confident that you can engage respectfully with people from different identity groups? In the last few years, many of us—especially White folks—have woken up to the limits of our own cultural competence. Maybe we’ve been called out for something we’ve said or done that caused harm to a friend or a colleague. Maybe we’ve witnessed someone else get called out for a microaggression or learned about microaggressions at a diversity training, and realized that we have done the same exact thing. Maybe we have discovered that a word that we commonly use is considered offensive. Those of us who are parents may be wondering how we can help our children do and be better than we are. We want our children to respond to diversity with respect and empathy, yet we fear that they will unintentionally say or do something that causes harm. How can we help our children navigate a diverse society, when we ourselves still have so much to learn? Over the past 18 months, my daughter and I have been growing our cross-racial and cross-cultural understanding side by side. It has been a joyful experience. In the spring of 2021 Kids for Racial Justice sponsored a parent workshop on “Reading for Joy: Using Books to Promote Children’s Cross-Racial Understanding.” We were honored to have Dr. Renata Love Jones and Dr. Nicholl Montgomery—brilliant, Black, language and literacy scholars, and educators— share their wisdom about the importance of centering joy rather than trauma when learning about other communities. They taught us that searching out joy allows us to see a people’s full complexity, beauty, genius, and humanity. Inspired by their message, as well as their delight in discussing children’s books by authors of color, I organized a “Reading for Joy” Parent/Child book club in my community. My 11-year old daughter and I have been joined by four of her friends and their parents. Over the course of our first year, I selected four books for the group to read. The books varied in genre including realistic fiction, fantasy, and humor. One was a graphic novel. All were written by authors of color and all centered joy. The book club meets on leisurely Sunday afternoons, usually in person, once on Zoom. We share food, we catch up, we laugh, we play, and we discuss the books that we have read. Our book discussions cover a lot of territory. There is time for the children and parents to raise the questions on their minds and time for me to bring up topics that will help us build empathy, respect, and connection across differences. We delve into both the characters and their contexts with the goal of deepening cross-racial understanding. We talk about the characters that we relate to, how we are similar and dissimilar from them, and what motivates their actions. We explore cultural, political, and historical contexts through conversations about and quick Google research into language, culture, and history. In May, we gathered to discuss New Kid, a graphic novel by Jerry Craft that uses humor, even as it illustrates the many microaggressions that its young protagonist experiences as one of only a few Black students at an elite prep school. Our conversation included much laughter about the comedic parts of the book, as well as serious discussion about the stereotyping and other microaggressions that Jordan endures. The children practiced recognizing, questioning, and standing up to microaggressions. The adults reflected on times when we ourselves have committed microaggressions similar to those in the books, and thought about how we can do better ourselves and how we can speak up when we witness microaggressions.

We learned. We laughed. We loved our time together. And we started planning for another year of joyful reading. What are you going to do? As the winter holidays approach, are you going to add joyful books by authors from a community other than your own to your holiday shopping list? Our Reading for Joy resources, developed by Dr. Jones and Dr. Montgomery, include book suggestions for Pre K–8th graders. We also have helpful guidelines for selecting books about communities other than your own and for engaging your child in conversation about these books. Are you curious about starting a Reading for Joy book club in your own community? If so, get in touch to learn more about the model.

1 Comment

Juneteenth was officially designated a federal holiday last year. However, it has been recognized as a day of celebration since 1865. It marks the date that enslaved Black people in Texas learned of their freedom, more than two years after Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. It has been commemorated by Black Americans ever since. This year, Juneteenth falls on Sunday, so the public holiday will be observed on Monday, June 20th. Your kids will be home from school and you may have the day off as well. Those of us who are not Black may well be wondering whether, and how, we should mark the Juneteenth holiday with our families. It’s a question that requires some thought. First, a word of caution. Juneteenth is a Black holiday. If you’re not Black, it’s not your holiday. (Check out Sa’iyda Shabazz’s powerful op-ed “Everyone Should Acknowledge Juneteenth — But Don't Celebrate It Unless You're Black.”) This year has already seen numerous attempts to appropriate and monetize the holiday (e.g. Juneteenth-themed ice cream from Walmart and a Juneteenth Soul Food event in Little Rock with White hosts). These attempts have been met with anger from Black communities. As the linked articles make clear, appropriation is not the right way to approach the holiday. But, just as importantly, we should not ignore the holiday. If we ignore it, we miss a natural opportunity to reckon with history and (re)commit to racial justice. So what should we do instead?

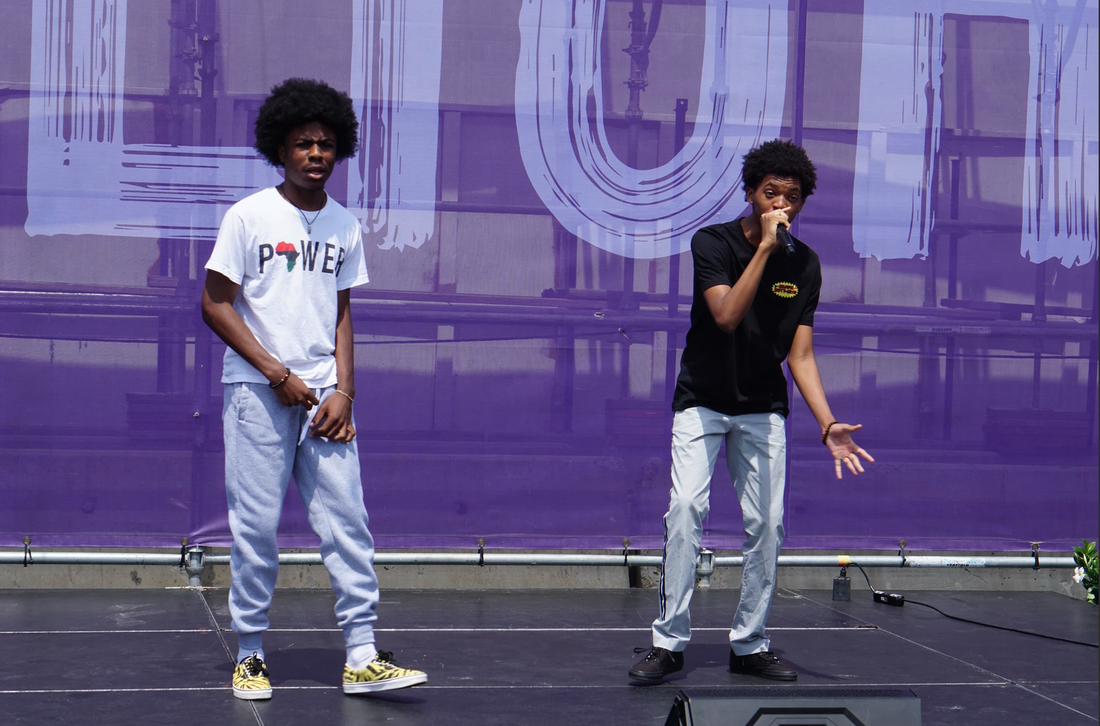

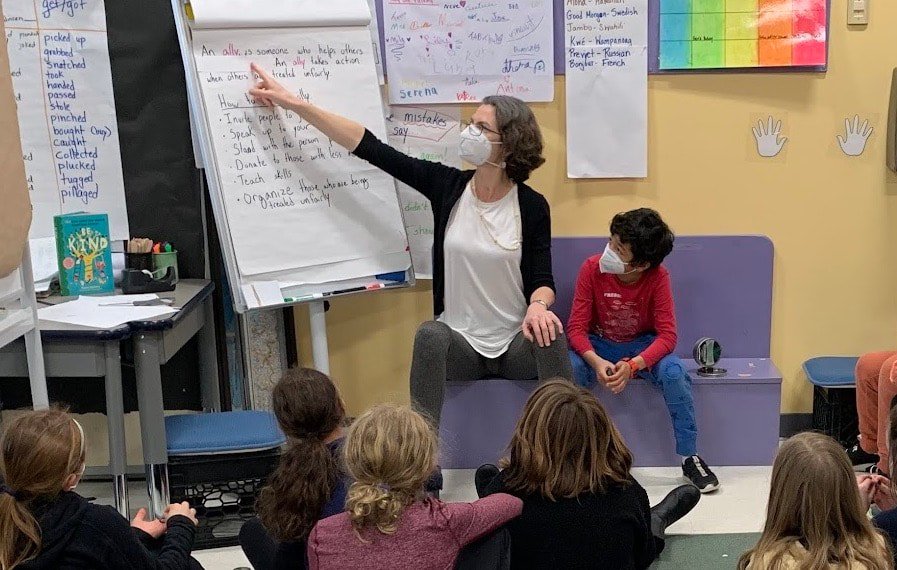

Books & More for Kids While it is convenient to find video read alouds of picture books online, we encourage you to (also) purchase the books, if possible, to support the authors and show that you value books like these. Juneteenth for Mazie, by Floyd Cooper. Picture book for ages 6–9.“ All Different Now: Juneteenth, the First Day of Freedom, by Angela Johnson, illustrated by E. B. Lewis. Picture book for ages 5–9. Juneteenth: Freedom at Last” from Minnesota History. This well-produced 6-minute video offers an overview of the holiday's history and a discussion of contemporary celebrations. It’s appropriate for children and adults alike. Time for Kids' article “A Juneteenth Celebration” discusses the origins of the holiday and how it is celebrated today. Resources for Adults So You Want to Learn about Juneteenth? Article from the New York Times. Why All Americans should Honor Juneteenth Historian Karlos K. Hill explains the history and significance of the holiday in a 7-minute video on Vox. Radio Boston Interview with Annette Gordon-Read, author of On Juneteenth  Family-Friendly Juneteenth Events Juneteenth Freedom Day: Celebrating Black Joy When: Sunday, June 19th, 1-3pm Where: Starlight Square in Central Square, Cambridge (84 Norfolk St.) What: We will center JOY with live performances from our youth. The Cambridge Families of Color Coalition is calling in the entire city to celebrate Juneteenth together in a joyous community. Juneteenth Celebration, Cambridge Public Library When: Saturday, June 18th, 12-2pm (and other events throughout the week) Where: Cambridge Public Library, Central Square Branch, 45 Pearl Street What: Storyteller Valerie Stevens, Music from Albino Mbie Band, Craft Table, Sidewalk chalk drawing, cupcakes Juneteenth Celebration in Newton When: Sunday, June 19th, 12-4pm Where: Newton North High School What: Food trucks, vendors, art, raffles, games, DJ Firestarta  Justice Squad holds a "Rally for Equality" Justice Squad holds a "Rally for Equality" In a month like this, it’s easy to despair. The combination of tragedy after tragedy and government dysfunction is grim. Black elders slaughtered while shopping for groceries. Young children and teachers mowed down in their own classroom. Political attacks on women’s rights, LGBTQ+ rights, and the climate. Rather than promoting the aims laid out in the Constitution—a more perfect Union, Justice, domestic Tranquility, common defence, the general Welfare, and the Blessings of Liberty—our government at best seems to do nothing and at worst chips away at our rights. We appear to be slipping ever closer towards a dystopian society. And yet I don’t despair. My work with children offers an antidote. The young activists in my Justice Squad groups inspire me with their passion and their can-do attitude. They believe that they have the power to change society, and so they take action. Currently, they are crafting a petition in defense of students’ right to learn about race, gender, and sexual orientation; raising money so that adults can fight for these rights; and creating a website filled with powerful calls to action. When my jaded adult mind doubts the efficacy of their actions, my heart reminds me that these loving and impassioned young people will become ever more capable and powerful as they grow up. Learning to be activists at 8, 9, and 10, what might they be capable of at 15, 18, or 25? “As long as we have breath in our lungs, we have to fight for justice,” writes anti-racist educator Tiffany Jewell. “When you are silent absolutely nothing changes.” So let's learn from the children’s example. Rather than giving into despair, rather than shutting down or turning away, let’s turn towards action. While the sheer number of issues that feel like they need our attention can be overwhelming, we can each choose one thing, and do something. Better yet, do something with the children in your life. Wondering how to do that? Read what I wrote here about taking action with children or this blog post about raising your child to be an activist. “Who has the responsibility to stand up to unfairness?” I posed this question to a group of 3rd and 4th graders. We had just finished reading Teammates, a picture book by Peter Golenbock that tells the story of Jackie Robinson and his White teammate Pee Wee Reese. The book highlights two moments when Pee Wee stood up for Jackie. First, Pee Wee refused to sign a petition that a group of their Southern teammates were circulating to get Jackie removed from the team. Later, when the Dodgers were playing the Cincinnati Reds, close to Pee Wee’s hometown in Kentucky, Pee Wee heard fans hurling abuse at Jackie. Saddened by the taunts and aware that it could have been his own friends and neighbors, Pee Wee walked over and put his arm around Jackie’s shoulders. With his gesture, Golenbock writes, Pee Wee said to the world, “I am standing by him. This man is my teammate.” With Jackie Robinson and Pee Wee Reese on their minds, the children turned to their neighbors to discuss who has the responsibility to stand up to unfairness. “Everyone.” “Everybody.” “We all do.” Similar words bubbled up from many of the groups. When we came back together to discuss the question, most of the children in this majority White classroom were in agreement that everyone should stand up when someone is being treated unfairly. However, as the discussion proceeded, some of the children began to offer more nuanced perspectives, with a focus on racism. A biracial child with Black and White parents spoke up. “Black people have to stand up. White people don’t have to.” The other children looked confused. I invited him to say more. He went on to explain that Black people have to stand up to racism, because it’s harming them, but White people don’t have to because it’s not impacting them in the same way. However, he clarified, White people should stand up to racism. Even if it’s not harming them in the same way, they should make the choice to stand up. It’s the right thing to do. This child raised a key point. People in historically dominant groups have a choice about whether or not to stand up to oppression that’s targeted towards other groups. While most of the children expressed the belief that everyone shares responsibility, would they actually take action if they witnessed others being mistreated? This is an important point for children to consider. Taking a stand against peers requires both conviction and courage. And what happens when doing the right thing comes at a personal risk? When Pee Wee Reese stood with Jackie in front of the abusive Reds fans, he risked alienating friends and family members who hated the idea of his playing on the same field as a Black player. Several children wondered aloud whether Pee Wee had faced repercussions. Did his family back home in Kentucky still accept him? A White child ventured that it was a risk worth taking; it would be better to have one good friend, like Jackie, than a bunch of racist or mean friends. Bringing us back to the question of responsibility, another White child made the case that it is particularly important for White people to stand up to racism because there are times when their voices have more power than the voices of people of color. Even though it’s not fair, she said, sometimes White people might be more willing to listen to another White person than to a person of color. This child’s spot-on analysis of power and privilege raised another important consideration for children from historically dominant groups. They may be more likely to stand up for others if they recognize their unearned privilege and the power that it gives them. Like this girl, children can simultaneously recognize their privilege, understand that it is unfair, and realize that they can use their privilege to make things more fair. This awareness may help them to act on their beliefs. This conversation occurred during the first in a series of three lessons that I taught on allyship.* In the subsequent lessons, I asked students to analyze power and privilege in different scenarios, to consider how allies can use their power and privilege as a force for justice, and to role-play ways to be an ally to peers. All children benefit from knowing about allies in racial justice work (as well as in other social justice movements). Psychologist Dr. Beverly Daniel Tatum explains that learning about White allies “who spoke up, who worked for social change, who resisted racism and lived to tell about it” helps White children get past feelings of shame and guilt that can come with learning about racism. These allies can show White children a positive way to be White. Children who are members of historically marginalized groups also benefit from learning about allies. Social justice educators Angela Berkfield and Chrissy Colón Bradt posit that learning about allies helps children see the potential for understanding and connection across differences, even as they become aware of the oppression that has been targeted at their group. Here are two proactive measures that parents and educators can take to teach children about allies:

Want to learn more? Join our mailing list to find out about upcoming parent workshops and kids' classes and to get family resources straight to your inbox. *Many people have raised objections to the use of "ally" in social justice situations, because it is frequently employed by people who claim that they support a cause or community, but do not actually engage in action. Some racial justice leaders, including Black Lives Matter co-founder Alicia Garza and education scholar Bettina Love, prefer the term co-conspirator to refer to those who show up and take responsibility for using their power for transformation. Others have suggested the term accomplice. As an educator, I believe that the actual term is less important than the concept. Whatever they may call themselves, I want my students to take action in the face of injustice.

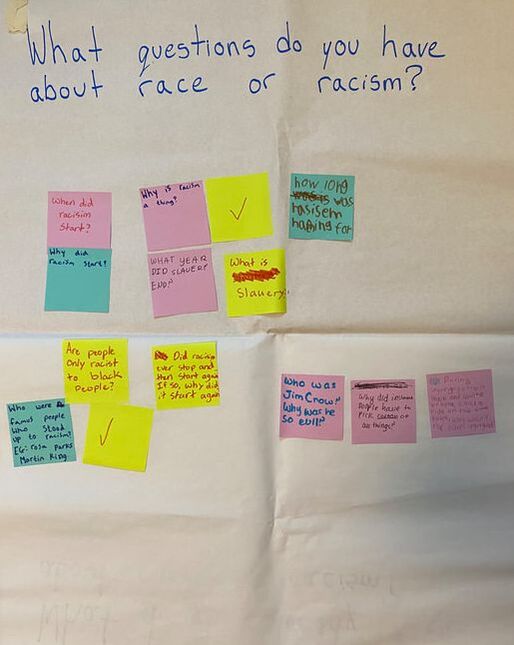

The Florida State Senate recently passed a bill that would prohibit public schools from teaching subject matter that could make children feel “discomfort” or “guilt” based on their race, sex, or national origin. This bill is part of a national trend. An Education Week analysis found that, in the past year, 37 states have introduced bills or taken other steps to restrict teaching critical race theory or limit how teachers can discuss racism and sexism. Fourteen states have successfully imposed these bans and restrictions. As I have written about previously here, White parents’ fears about their children's discomfort are often greatly overblown. Yes, children may experience some feelings of guilt as they learn about the terrible things that White people have historically done to people of color. However, learning this history can actually be an energizing experience for children, inspiring them to take antiracist action. Earlier this month, I invited the 3rd, 4th, and 5th graders in my Justice Squad group to share their questions about race and racism. Their questions poured out:

These questions reveal how curious children are about the origins and history of racism in this country. The little bit that they have already learned has left them confused and concerned. Consider the questions: “Why did racism start?”; “Why is racism a thing?”; and “Why did Whites think they were better?” To these children, most of whom are White, the idea that one group of people would consider themselves superior to another on the basis of skin color is nonsensical and abhorrent.

Growing up in the liberal-leaning Boston suburbs, these children are probably being taught that all humans are equal. That doesn’t mean that our work is done. Research into how children learn about race shows that even when they are explicitly taught messages of equality, they absorb tacit messages that can lead to the development of racial biases. Living in a society shaped by structural racism, children have to make sense of the inequality that they see around them. In her research on White children’s racial socialization, sociologist Margaret Hagerman has found that children often explain the persistence of inequality with racial stereotypes that blame people of color. So what can parents do? We can make sure our children have opportunities to ask and find answers to their questions. That means bringing books and other media that address BIPOC history into our homes and talking about them with our kids. It also means letting our children’s schools know that we want our children to learn this history, and supporting teachers who tackle these topics. Will it make children uncomfortable to learn about this history? It certainly might. But they want and need to know about it. Florida state Senator Shevrin Jones, the state’s Senate Education Committee vice chair and its only Black member, criticized the Florida bill: “They are talking about not wanting White people to feel uncomfortable? Let’s talk about being uncomfortable. My ancestors were uncomfortable when they were stripped away from their children.” It’s time to stop prioritizing White children’s comfort. They can handle the discomfort of learning the truth. Instead, how about we prioritize the humanity of all our children. That means teaching true history, the history our kids want to learn, so that our children can begin to undo the harms that have been perpetuated throughout that history and work for a more racially just future. “Whenever I talk to my daughter about racism, she wants to know what we can DO about it. Honestly, I don’t know what to tell her.” This is a common refrain among the parents I talk to. Children have an innate sense of fairness. During the elementary years, this sense of fairness begins to extend beyond themselves to consideration of others. By 8 or 9, many children are capable of thinking about societal issues and are upset to learn about injustice in the world. At the same time, children of this age are beginning to look for ways to reach out to others and make a difference in the world. Many upper-elementary and middle-school-aged children are naturally drawn to activism. Parents, on the other hand, may feel powerless to effect change. Adults are often discouraged by the enormity and complexity of problems such as racism. It can be hard to believe that individual acts actually make a difference. For the sake of your children (and your own mental health!), I encourage you to seek out opportunities to participate in meaningful social action, no matter how small.* So where do you start? I recommend plugging into organizations and projects that are already in motion. There’s power in numbers and joining with others in common cause can help to dispel the depressing feeling that it is you against the world. The upcoming MLK Day national holiday presents a perfect opportunity to take action in community with others. MLK Day is officially designated as a national day of service—the only holiday to have that designation. It has become a day to remember Dr. King’s work and, just as importantly, to continue along the path he paved towards justice. Many organizations sponsor or organize community service events on or around MLK Day that are open to all comers, including children.

How does an experience like this address a child’s desire to do something about racism? Many of the youth who work with More Than Words have been harmed by structural racism. Their opportunities have been limited due to generational poverty, the school-to-prison pipeline, and other broken systems. As my kids and I worked on the book drive, we had several conversations about structural racism, privilege, and our shared humanity. I did my best to help the kids understand that, by helping More Than Words, we were helping create opportunities for youth marginalized by racism.** Did we solve racism? Of course not. But we did build our muscles for engaging in ongoing antiracist action. Occasions like MLK Day are an established way to get involved in the work that needs to be done every day. Martin Luther King Jr. once said, “If I cannot do great things, I can do small things in a great way.” What small things will you and your family do this MLK Day to serve justice in a great way? Hit the contact us button and request to be added to my Family Action mailing list. Approximately twice a month you will receive an email with family-friendly opportunities to take action for racial justice. Many of the ideas for action come from BIPOC-led groups in the Boston area that are doing racial justice work. Do you have an idea to share? I’d love to hear from you. -Meredith Founder & Director *If and when possible, seek out racial justice action that is led by people of color from the communities most impacted.

**Ideally action should be accompanied by learning and reflection. Learn about those who are most impacted by the problem. Explore the root causes of problems. Consider your own role in the problem. Last spring, I was chatting on the sidelines of my son M’s soccer game with his friend Ethan’s mother, Cindy*, who, like me, is White. I had previously invited Ethan to participate in a Justice Squad pilot with M and some of their mutual friends, but Cindy had declined, claiming that Ethan was overcommitted and Zoomed-out. But that April day on the soccer sidelines, Cindy revealed an additional motive. “Ethan’s teacher has been talking about racism a lot,” she shared. Remote school had given Cindy a close-up view of Ethan’s first grade class. She told me that the kids had learned about Ruby Bridges, who, at age 6, had faced down an angry White mob every morning for months, as the first Black child to integrate her New Orleans elementary school. Ethan’s teacher had also read aloud Something Happened In Our Town, which addresses a police shooting in contemporary America. “I don’t know,” Cindy fretted. “I think that all this is making Ethan and the other kids feel bad about themselves.” “Really?” I replied. “I don’t see a lot of that with the kids in Justice Squad. We make sure to pair learning about racism with taking action for racial justice. Has Ethan’s teacher made any opportunities for the kids to take action?” Cindy recollected that Ethan had made a Black Lives Matter sign and the class had also written letters condemning racism. Our conversation petered out, and we returned to watching the soccer game. I wasn’t surprised by Cindy’s concern. Parents want to protect their kids. We worry about their fragile bodies and their innocent minds, and we try our best to shield them from harm. We fear that the truth about racism will cause them pain. Often, our concern comes from our own experience of losing our racial innocence. For some of us, in particular White people and some non-Black people of color, the last few years have included a lot of uncomfortable learning about the true history of racism in this country. Discovering the truth about racism and White supremacy brings up unpleasant feelings, including confusion, sadness, anger, and helplessness. For those of us with racial privilege, there can also be a lot of guilt and shame. Naturally, if we associate race talk with painful emotions, we may feel an impulse to protect our kids from experiencing those same emotions. In particular, we may be reluctant to expose them to something that might cause them shame about who they are. However, our worries about our children’s feelings are often overblown. Let me return to my story to illustrate. Perhaps ten minutes passed before Cindy turned back to me. “I’ve been thinking about what you said. You know what? I don’t know that Ethan is feeling bad about being White. That might just be me.” Cindy’s revelation was huge. She recognized that her son had been participating in conversations about race and racism without feeling guilt or shame. She had been projecting her own feelings onto Ethan with no evidence that he felt the same way. In my experience as a racial justice educator, I have seen very few instances of guilt or shame among White children. So why don’t children like Ethan react the same way as their parents? I attribute this to a few factors.

Our children are not as fragile as we think they are. When racial justice education is approached with care and expertise, it can be a positive, and even empowering experience for children. White parents, how have your kids engaged with the topic of racism? Have they asked questions? Did they wonder how to fix it? Children’s desire to take action creates a real opportunity for all of us. If we heed our children’s call to take action, we may be able to overcome our own guilt and shame, as we commit to working towards racial justice together. Want to learn more? Join our mailing list to find out about upcoming parent workshops and kids' classes and to get family resources straight to your inbox. *Names have been changed to preserve anonymity.

For many, Thanksgiving is a time to gather with loved ones and express gratitude for our blessings. This year, many are anticipating the return of beloved traditions around food, family, and footfall that we had to skip last year. The holiday also, undeniably, represents a shameful period in American history.

Thankfully most schools here in Massachusetts have abandoned some of the most cringe-worthy approaches towards teaching kids about Thanksgiving. We don’t see a lot of construction paper headdresses or class plays where the Native characters have to act grateful to the colonists for “civilizing” them. However, there’s no getting around the fact that Thanksgiving represents the successful launch of the colonial project in what is now the United States, leading to the genocide of millions of Native people, the theft of Native lands, and the attempted erasure of Native cultures. So what is a parent who cares about racial justice to do? Rather than celebrating Thanksgiving, some families make the choice to commemorate the National Day of Mourning, when indigenous people and their allies gather in Plymouth to honor indigenous ancestors and to protest against the racism and oppression that indigenous people continue to experience worldwide. Others continue to embrace the holiday, but make the effort to have honest conversations with their children about the brutal history that it glorifies. (Find some resources to support talking with your kids here and here.) But what if we also treated the holiday as a chance to take positive action to support Indigenous communities? I recently learned about the Black Swamp Rematriation Project*. In collaboration with the Agrarian Trust, members of the Massachusett and Nipmuc tribes are working to purchase and preserve a 64-acre plot of farmland on their traditional lands. The vision for this land is to restore the matriarchal principles of earth-centered stewardship. They plan to carry out activities including sheep farming, growing traditional varieties of corn, squashes, beans, and grains, starting a small nursery and orchard, as well as indigenous ceremony and indigenous art-making. This is one effort in the larger #LandBack movement, which has worked for generations to get Indigenous Lands back into Indigenous hands. The Black Swamp Rematriation Project* presents a concrete way to support Indigenous people in my neck of the woods. I seized the opportunity to take action with my family. I started with a conversation with my 10-year-old. As we were walking home from the orthodontist, I asked her what she remembered about the first people who lived on this land. Having studied the Wampanoag in school in both 3rd and 4th grades and written a report about their food and medicine, she was able to recall a lot of information. I then inquired if she knew what had happened once English colonists arrived in the region, and we discussed how the English had claimed the land throughout our region for their own, pushing Native tribes off their traditional hunting grounds. I made sure to express my sadness and outrage over the way that the Natives were treated. With that context in place, I gave a quick overview of the Black Swamp Rematriation Project, and asked her if she’d be interested in donating to support it. Without hesitation, she responded, “Yes!” Back at home, my daughter and I went onto the website together to learn more about the project. After watching a short video and reading about the plans for the site, I asked her how much she would like to donate. She hedged and asked me what I thought, but I insisted that she make this decision for herself, as she’d be donating her own money. Ultimately, she decided on $20 of her “give away money” (my kids get a three-part allowance: money to spend, to save, and to give away), which we added to the funds that I was planning to donate, and we made a joint donation then and there. This approach towards Thanksgiving sits right with me. When White parents engage our kids in honest conversations about our history as colonizers, it can surface uncomfortable feelings like sadness, guilt, and anger. These feelings aren’t helpful by themselves. (I’ll write more about this in an upcoming post.) What IS helpful is channeling these emotions into action. Sadness, guilt, and anger can motivate us to take concrete steps to remedy past wrongs and work to create a better future. From now on, I plan to frame Thanksgiving as a call to action. *Contact us to get the password to access the Black Swamp Rematriation Project webpage. We are pleased to announce that Anti-Racist Academy is now Kids for Racial Justice. At Kids for Racial Justice, we pair learning with action. We believe that it is not sufficient for children to understand intellectually that racism is wrong or to feel sadness, anger, or indignation when confronted with the evidence of racism. Outrage alone will not end racism. Instead, we seek to support children in actively working for racial justice in their schools, communities, and beyond. Our new name captures our focus on action, emphasizing the racially just future that we hope to empower children to build.

|

Archives

November 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed