|

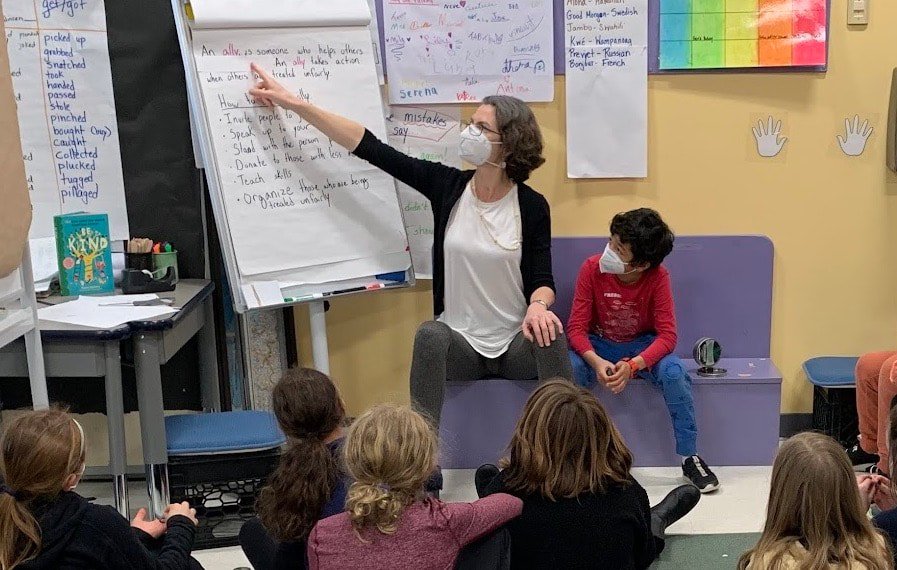

“Who has the responsibility to stand up to unfairness?” I posed this question to a group of 3rd and 4th graders. We had just finished reading Teammates, a picture book by Peter Golenbock that tells the story of Jackie Robinson and his White teammate Pee Wee Reese. The book highlights two moments when Pee Wee stood up for Jackie. First, Pee Wee refused to sign a petition that a group of their Southern teammates were circulating to get Jackie removed from the team. Later, when the Dodgers were playing the Cincinnati Reds, close to Pee Wee’s hometown in Kentucky, Pee Wee heard fans hurling abuse at Jackie. Saddened by the taunts and aware that it could have been his own friends and neighbors, Pee Wee walked over and put his arm around Jackie’s shoulders. With his gesture, Golenbock writes, Pee Wee said to the world, “I am standing by him. This man is my teammate.” With Jackie Robinson and Pee Wee Reese on their minds, the children turned to their neighbors to discuss who has the responsibility to stand up to unfairness. “Everyone.” “Everybody.” “We all do.” Similar words bubbled up from many of the groups. When we came back together to discuss the question, most of the children in this majority White classroom were in agreement that everyone should stand up when someone is being treated unfairly. However, as the discussion proceeded, some of the children began to offer more nuanced perspectives, with a focus on racism. A biracial child with Black and White parents spoke up. “Black people have to stand up. White people don’t have to.” The other children looked confused. I invited him to say more. He went on to explain that Black people have to stand up to racism, because it’s harming them, but White people don’t have to because it’s not impacting them in the same way. However, he clarified, White people should stand up to racism. Even if it’s not harming them in the same way, they should make the choice to stand up. It’s the right thing to do. This child raised a key point. People in historically dominant groups have a choice about whether or not to stand up to oppression that’s targeted towards other groups. While most of the children expressed the belief that everyone shares responsibility, would they actually take action if they witnessed others being mistreated? This is an important point for children to consider. Taking a stand against peers requires both conviction and courage. And what happens when doing the right thing comes at a personal risk? When Pee Wee Reese stood with Jackie in front of the abusive Reds fans, he risked alienating friends and family members who hated the idea of his playing on the same field as a Black player. Several children wondered aloud whether Pee Wee had faced repercussions. Did his family back home in Kentucky still accept him? A White child ventured that it was a risk worth taking; it would be better to have one good friend, like Jackie, than a bunch of racist or mean friends. Bringing us back to the question of responsibility, another White child made the case that it is particularly important for White people to stand up to racism because there are times when their voices have more power than the voices of people of color. Even though it’s not fair, she said, sometimes White people might be more willing to listen to another White person than to a person of color. This child’s spot-on analysis of power and privilege raised another important consideration for children from historically dominant groups. They may be more likely to stand up for others if they recognize their unearned privilege and the power that it gives them. Like this girl, children can simultaneously recognize their privilege, understand that it is unfair, and realize that they can use their privilege to make things more fair. This awareness may help them to act on their beliefs. This conversation occurred during the first in a series of three lessons that I taught on allyship.* In the subsequent lessons, I asked students to analyze power and privilege in different scenarios, to consider how allies can use their power and privilege as a force for justice, and to role-play ways to be an ally to peers. All children benefit from knowing about allies in racial justice work (as well as in other social justice movements). Psychologist Dr. Beverly Daniel Tatum explains that learning about White allies “who spoke up, who worked for social change, who resisted racism and lived to tell about it” helps White children get past feelings of shame and guilt that can come with learning about racism. These allies can show White children a positive way to be White. Children who are members of historically marginalized groups also benefit from learning about allies. Social justice educators Angela Berkfield and Chrissy Colón Bradt posit that learning about allies helps children see the potential for understanding and connection across differences, even as they become aware of the oppression that has been targeted at their group. Here are two proactive measures that parents and educators can take to teach children about allies:

Want to learn more? Join our mailing list to find out about upcoming parent workshops and kids' classes and to get family resources straight to your inbox. *Many people have raised objections to the use of "ally" in social justice situations, because it is frequently employed by people who claim that they support a cause or community, but do not actually engage in action. Some racial justice leaders, including Black Lives Matter co-founder Alicia Garza and education scholar Bettina Love, prefer the term co-conspirator to refer to those who show up and take responsibility for using their power for transformation. Others have suggested the term accomplice. As an educator, I believe that the actual term is less important than the concept. Whatever they may call themselves, I want my students to take action in the face of injustice.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

November 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed